Financing mobility: an overview of European and national programs supporting mobility

As previously described in the first article of this series, “The reference pilots for the development of the “Italian Way to Connected Mobility”: a mapping of more than 160 cases”, the second edition of the initiative “The Italian Way to Connected Mobility” began with the description of use cases in an aim to highlight the main insights and opportunities associated to the development of new cases of smart and connected mobility. To this end, The European House – Ambrosetti has mapped the most successfull use cases to identify the potential applications and benefits of Connected Mobility projects.

Alongside the mapping of the case studies, The European House – Ambrosetti has conducted an in-depth analysis of European Plans to finance the mobility of the future. This goal of this work was to identify where Europe and some benchmark countries (Italy, France, Spain and Germany) are directing public investments for the development of new mobility paradigms. Furthermore, the analysis aims to ascertaining the extent to which connected technologies are being taken into account as innovation levers in the huge investments in mobility and transportation planned both at the national level and by the main European countries.

The present analysis identified the necessary elements enabling the design and implementation of mobility initiatives that involve connected technologies. First, infrastructures capable of acquiring and exchanging data with the external ecosystem are necessary. Second, due to their very nature, connected mobility projects must fall on an “ecosystem” of stakeholders – citizens, companies, public institutions – who voluntarily share their personal data for the optimization of services. For instance, with reference to the management of the transition to electric motorizations, a public transport company can define the route of battery-powered vehicles on the basis of a real-timesurvey of consumption data; Public Administrations can identify optimal areas for charging stations by analyzing route statistics and estimates of residual charge levels; citizens can quickly identify available strales for charging based on their location. Finally, local Government play a crucial role in the promotion of a modern vision of mobility, by guiding citizens during the phases of the process of change. To this end, it is necessary that public and private entities are aware of the potential of connected mobility technologies that can be applied to their area, in order to promote new use-cases that are capable of solving problems otherwise difficult to manage.

Identifying new mobility patterns can galvanize the objectives of the European Commission’s policy document“Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy”[1] published in December 2020, which promotes the development of sustainable, smart and resilient mobility projects at the European level by 2050. Notably, the document integrates valuable indications related to several areas that are often analyzed separately, such as the diffusion of private and public zero-emission vehicles, the development of new types of mobility and self-driving vehicles, the diffusion of connected technologies in mobility, etc. This document highlights once more the relevance of Public Institutions in developing and promoting highly innovative visions of mobility projects, both on a national and local scale.

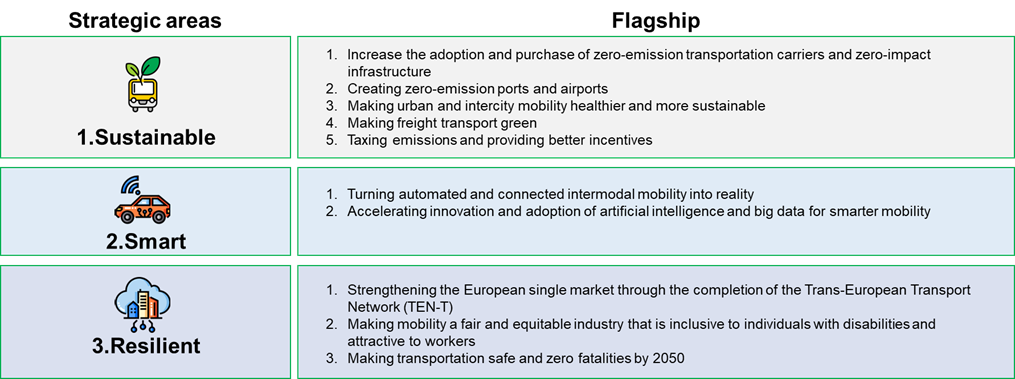

The policy document pointed out that the “twin transition” – digital transition and green transition – has a central role in promoting a reduction in emissions and an improvement in the entire transportation structure.[2] Fostering the transition to digitized models that enable the decarbonization of the transports sector underpins ten ambitious milestones – to be achieved between 2030 and 2050 – ranging from emission neutrality in road transports to the full implementation of trans-European corridors, via the development of autonomous mobility.[3] To ensure the achievement of these milestones, the European Strategy is divided into three strategic areas that are complementary and synergistic with each other: sustainable mobility, smart mobility and resilient mobility. These areas include ten components – “flagships” – thatpoint atinteresting strategies for the digital and ecological transition, but nevertheless lack specific initiatives to implement intermodal and fully integrated mobility models in urban ecosystems.[4]

Figure 1: Articulation of the 10 flagships of the Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy. Source: elaboration The European House – Ambrosetti on data from the European Commission, 2022

To achieve the goals set by the Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy, the European Commission has deployed a substantial plan of economic and financial aid of 2.018 billion euros, divided mainly between:

- 1,211 billion euros included in the EU budget for 2021-2027;

- 807 billion euros set up by the Next Generation EU fund.

Within this plan, the three key programs that encapsulate the main areas of intervention in the European Mobility Strategy are:

- Connecting Europe Facility (CEF), €25.8 billion included in the EU budget (2% of the budget) for the period 2021-2027, and broken down into grants aimed at the development of sustainable high-impact infrastructure for the entire EU territory. As of April 2022, the CEF has 3 calls for proposals underway related to the development of intelligent incident detection and warning systems, the development of cross-border renewable energy sharing systems, and the development of alternative fuel supply infrastructure. The Reference Entity for these funds is the European Climate Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency.[5]

- Cohesion Fund (CF)[6] and European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), both part of the €274 billion allocated by the EU budget to regional cohesion (accounting for about 23 percent of the entire budget), devoting €32.5 billion (accounting for 67 percent of the CF) and €192.4 billion (accounting for 85 percent of the ERDF), respectively, to mobility on a regional and urban scale, with the goal of connecting all European regions to the TEN-T network by 2030.[7]

- Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), acentral part of the Next Generation EU fund, divided into €338 billion of grants and €385.8 billion of loans, for a total of €723.8 billion (accounting for about 90 percent of the Next Generation EU fund), the management of which is entrusted to Member States through the implementation of National Recovery and Resilience Plans (NRPs) – which were the main focus of this analysis due to the amount of allocations specifically dedicated to mobility.

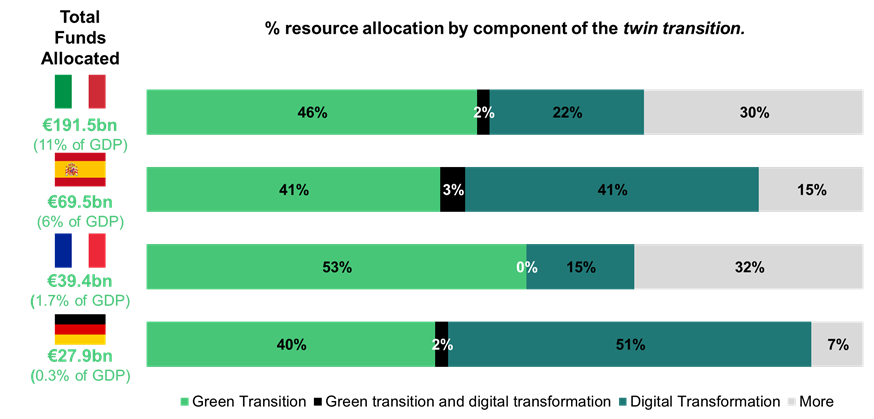

The analysis of the Recovery and Resilience Plans submitted by the main EU countries – Italy, Spain, France and Germany – led to interesting insights regarding the different approaches in the allocation of resources and the management of mobility aspects. In fact, going back to the concept of “twin transition” and the way in which it was implemented in the pilot cases analyzed – that is, through a “green” and a “digital” component operating synergistically – it is quite surprising that, within the NRPs presented by the benchmark countries, the project initiatives where the hybridization of the two components is found accounts for 2-3% of the total resources allocated, with France even choosing not to allocate resources to hybrid projects, and opting instead for investments centered on the green transition of major transport infrastructures: railways, highways and ports.

Figure 2: Percentage allocation of funds by investment components relevant to the “twin transition.” Source: elaboration The European House – Ambrosetti on data from Intesa Sanpaolo and the European Commission, 2022

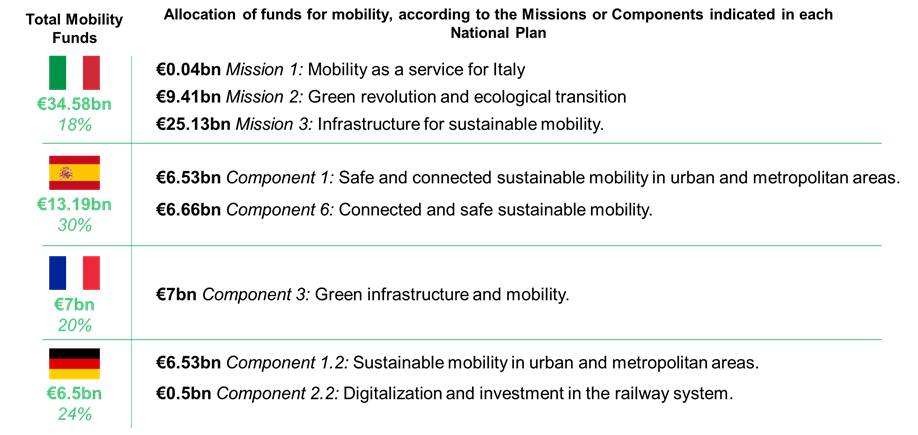

When compared with other public initiatives, it emerges how this figure reflects precise strategic choices by governments and institutions, that go beyond the use of European funds. In fact, within the initiatives strictly related to mobility (accounting for 20 percent to 30 percent of the total amount of Plans submitted), the issue of connected mobility was often a marginal topic.

Notably, only in few cases the use of connected technologies for mobility been explicitly included as a requirement for project (as in the Spanish PNRR). This exhacerbates the need to increase awareness with respect to the transformative potential of connected technologies, especially among Public Administrations called upon to define projects eligible for funds.

Figure 3: Allocation of mobility-related funds in the various NRPs of the benchmark countries. Source: elaboration The European House – Ambrosetti on national PNRR data, 2022

In this framework, the Italian PNRR differs slightly from its European counterparts, not so much in the allocation of funds for mobility – which is the largest among the countries considered (over 34 billion Euros) – but rather in the fact that Mobility as a Service, is treated in a dedicated investment program, which, however, remains a single item: Investment 1.4.6 “Mobility as a Service for Italy”. The investment, for which the NRP allocates 40 million euros, fits within Mission 1 with the goal of creating a national MaaS infrastructure. The first tranche of funds, 16.9 million euros, was allocated on Oct. 29, 2021 through a call for tenders aimed at identifying three pilot projects – including one in southern Italy – to be implemented in as many technologically advanced metropolitan cities (“leading” cities) as possible, in an aim to introduce the Mobility as a Service paradigm in local transport systems[8]. The profile of the winning cities – Milan (MaaS and Living Lab[9] ), Naples (MaaS) and Rome (MaaS)[10] – suggests that the strategic line adopted by the Ministry for Technological Innovation and Digital Transition is to favor projects to be implemented in large metropolitan contexts. This strategy was again confirmed in the call for proposals published last May 2, 2022, which reiterates the theme of developing pilot projects in already technologically advanced metropolitan contexts.

It is considered important to point out that, in the Call’s understanding, MaaS is limited to the integration of multiple public and private transportation services, accessible to the end user through a single digital channel. Such a view turns out to be limiting with respect to the broader potential of connected mobility, in which data sharing can enable the creation and execution of new types of mobility.

Considering the Italian scenario, in order to make this paradigm effective, the development in the most advanced cities should be combined with regional-scale approaches that take into account the peculiarities of smaller cities and suburban areas. Focusing only on the medium-to-large urban areas limits the possibility of implementing distributed mobility and commuting projects. On the contrary, other European countries such as Spain, a differentiated approach has been adopted for large and small cities, directly entrusting even small to medium-sized local administrations with the definition of projects that can be eligible for PNRR calls.

Finally, connected mobility could take on further relevance within the NRP if it were to be included within other Missions as well, as a prerequisite for the execution of projects related to fleet transition and the strengthening of the transport infrastructure network. For instance, looking again at the Spanish PNRR, within both reference components for mobility development (the 1 and 6), the use of connected technologies is considered as a requirement to be included in the project plans.[11]

Two main components emerge from the analysis of the French Recovery Plan, which includes 7 billion euros to be allocated for national mobility development:

- Preponderance of the “green” aspect of the twin transition, to which the NRP devotes about 50 percent of its resources, compared with about 40 percent for its Italian counterpart;

- Strong mix of direct investment (taking up slightly less than half of the allocated resources) and tax breaks for private enterprises.

With this in mind, in order to find initiatives in France that could echo what we have seen in Italy and Spain, it is necessary to look beyond the Plan National de Relance et de Résilience, focusing instead on the loi d’orientation des mobilités (Mobility Orientation Law), enacted in 2019 and providing for a total investment of €14.3 billion for the period 2023-2024, with the aim of:

- Develop multimodal interchange and public transport hubs, with a priority on serving key urban policy neighborhoods;

- support innovations, new mobility services, and autonomous and connected vehicles;

- boosting active mobility modes, particularly biking and walking.[12]

Germany has instead preferred not to make use of its Recovery and Resilience Plan for interventions in the area of connected mobility. In fact, the Plan appears to be focused almost solely on supporting the automotive industry in its transition to electric mobility with added specific interventions on the development of hydrogen and the rail system. From this perspective, innovation in local public transport is managed by the governments of the Länder (finding many similarities with both the Spanish case, as well as the French loi d’orientation des mobilités), which are entrusted with the task of drafting local transport plans and the coordination of service operators. The federal government, on the other hand, is given management and authority over major infrastructure and long-distance transports. This strategic approach is also confirmed in the way funds for mobility development are allocated: the 269.6 billion euros allocated by the Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan 2030 (FTIP), sponsored by the Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure, is almost exclusively for the maintenance and upgrading of the road fabric (49.3 percent of funds), and the federal rail system (41.6 percent of the total)[13] .

Similarly, within the 27.9 billion euros of the Deutscher Aufbau und Resilienz plan (DARP), it can be seen that, in line with the priorities drawn up in the federal plan, there is a clear intention to resume the goal of supporting the German automotive industry through incentives and tax relief (covering about 60 percent of the total mobility funds provided in the DARP), while high-innovation-load initiatives in the area of connected mobility fall under the initiative of individual states, among which Hamburg stands out. The latter, thanks to its connected and multimodal mobility policies, ranks as the clear leader in Bitkom’s (the German digital industry association) Smart City Index 2020. Since the launch of Hamburg’s ITS-strategy: Providing Future Urban Mobility and Logistics Solutions, adopted by the Senate in 2016, Hamburg has completed 63 projects in the area of connected mobility. In addition, the City of Hamburg has launched another 95 projects to be developed with investments of €60 million across 7 fields of action[14] .

In conclusion, the excursus, made on public initiatives to support the development of connected mobility within the main European countries, highlighted how the involvement of small to medium-sized urban realities is the key strategy for the development of truly integrated mobility systems.

The main case studies, presented in our previous article “Reference pilots for the development of the “Italian Way to Connected Mobility”: a mapping of more than 160 cases,” highlighted the centrality of public actors in promoting new initiatives with multi-stakeholder involvement, as well as the importance of working at the local level to identify real development needs and opportunities. This logic should be embraced in the implementation phases of the NRP so as to ensure the achievement of the milestones while generating important spillovers throughout the territory.

Finally, it is important for the NRP to provide reward mechanisms for those projects that include the use of connected technologies as a lever to transform mobility toward OCTO’s Vision Zero: zero pollution, zero traffic, and zero accidents.

Author:

The European House – Ambrosetti

[1] Source: EU Mobility Strategy, European Commission, 2022.

[2] Source: elaboration of The European House – Ambrosetti on data from European Commission and European Environment Agency, 2022.

[3] These milestones include: (i) achievement of 30 million operational zero-emission cars on all European roads by 2030; (ii) achievement of energy neutrality in more than 100 cities by 2030; (iii) doubling of high-speed rail traffic by 2030; (iv) achievement of energy neutrality on all commuter routes under 500km by 2030; (v) implementation of large-scale autonomous moblity by 2030; (vi) placing the first 0-emission vessels on the market by 2030; (vii) placing the first 0-emission vehicles on the market by 2035; (viii) full achievement of green transition in the automotive sector by 2050; (ix) doubling of European rail mobility by 2050; and (x) full implementation of the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) by 2050. Source: elaboration The European House – Ambrosetti on European Commission data, 2022.

[4] Source: elaboration of The European House – Ambrosetti on Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internazionale Zusammenarbeit, 2022.

[5] Source: elaboration The European House – Ambrosetti on European Commission data, 2022.

[6] For the Cohesion Fund, the European Commission’s implementing decision establishes the following member states as beneficiaries of the Cohesion Fund: Bulgaria Czechia Estonia Greece Croatia Cyprus Latvia Lithuania Hungary Malta Poland Portugal Romania Slovenia and Slovakia. As for Italy, the beneficiary regions are: Umbria Marche Abruzzo Campania Puglia Basilicata Calabria Sicily and Sardinia. Source: elaboration The European House – Ambrosetti on EUR-Lex data, 2022.

[7] Source: elaboration The European House – Ambrosetti on European Commission data, 2022.

[8] Source: elaboration The European House – Ambrosetti on data from Ministry for Technological Innovation and Digital Transition, 2022.

[9] According to the definition given by the Ministry for Technological Innovation and Digital Transition, Living Lab means “an urban laboratory where innovations and emerging technologies in the field of mobility can be tested under real conditions, in co-creation with users.” Source: elaboration The European House – Ambrosetti on data from Ministry for Innovation and Digital Transition, 2022.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Source: elaboration The European House – Ambrosetti on data Ministerio de Trasnportes Movilidad y Agenda Urbana, 2022.

[12] Source: elaboration The European House – Ambrosetti on Legifrance data, 2022

[13] Source: elaboration The European House. – Ambrosetti on data from Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure, 2022.

[14] The 7 fields of action are: Data and Information Collection (e.g., Urban Data Platform Hamburg); Automated Traffic Counting with Thermal Imaging Cameras; Intelligent Traffic Control and Guidance; Intelligent Infrastructure (Hamburg Box); Intelligent Parking (SynCoPark); Mobility as a Service (HVVV Switch, on-demand shuttles); Automated and Networked Driving (HEAT).