Researchers Ana Louro, Nuno Marques da Costa and Eduarda Marques de Costa, from de Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal, published an article on MDPI on may 23 2019. The article provides an a-up to date review on this issue. Here there are some of the key issues.

The present study covers the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, Portugal, and its municipalities. The intention of this paper is to understand if sustainable urban mobility policies at the municipal and metropolitan levels contribute to healthy cities.

Definition principles: “A healthy city is one that is continually creating and improving those physical and social environments and expanding those community resources which enable people to meet their own needs”

“A sustainable city is often defined as a city designed with consideration of local and global environmental impact, guided by urban sustainability visions and targets.

The definitions of sustainable cities and healthy cities and the principles that drive them reveal common points that prove their symbiotic relationship.

Four key points stand out:

1) the multi-temporal perspective, which simultaneously considers interventions and results in the short term and the long term, the present and the future, and this generation and the next ones;

2) the multi-sectoral perspective, which highlights that sustainable cities require relationships among several sectors in the environmental, economic, and social domains

3) the multi-level perspective, which, similar to the context of sustainable development, raises the level of local initiatives, such as sustainable communities or neighborhoods, to the global scale, whereas the Healthy Cities movement intends to exert its effects starting from the individual level, then moving to the community level, until finally reaching the global or ecosystem level; and, lastly,

4) the common view that neither approach is focused on achieving specific goals but rather on the realization of a continuous improvement process applied to cities and the quality of life of their inhabitants.

In turn, there are many consequences that are contrary to the principles of healthy cities, and they can be organized into four main areas: (a) the social area, with consequences such as social exclusion (b) the health area encompasses consequences in the form of a great variety of diseases, such as respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases], neurological diseases, behavioral and psychological disorders, and obesity; (c) from the economic area emerges the loss of local amenities, infrastructure, and material costs, fuel costs, and time costs (d) finally, in the environmental area, the decline in green spaces and open spaces, water and soil contamination, and global warm.

The concept of sustainable mobility assumes that all citizens can choose accessibility and mobility options that are safe, comfortable, timely, and affordable, and that simultaneously contribute to environmental protection by having high levels of energy efficiency and reduced environmental impacts.

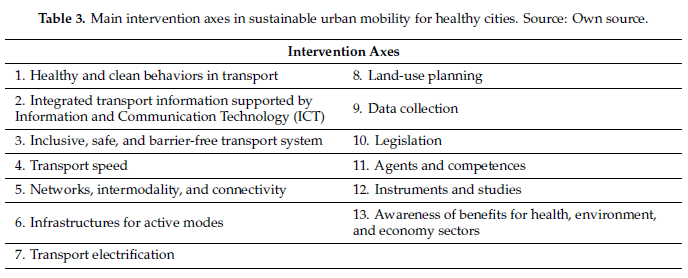

Intervention axes: The authors highlight the identification of 13 intervention axes in sustainable urban mobility for healthy cities.

Intervention:

- Axis 1, “Healthy and clean behaviors in transport”, promotes, for instance, safe driving behaviors by individuals free from the harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and drugs.

- Axis 2, “Integrated transport information supported by Information and Communication Technology (ICT)”, includes initiatives that provide real-time information about routes and schedules or about support infrastructures such as parking, electric vehicle loading, or bikesharing.

- Axis 3, “Inclusive, safe, and barrier-free transport systems”, highlights initiatives to make the system more inclusive (e.g., level crossing and walking), and safer (e.g., lane separation, protection of bicycle lanes)

- Axis 4, “Transport speed”, is linked to the creation of public transport lines (priority or exclusive routes) or areas of reduced flow and the speed of motorized modes.

- Axis 5, “Networks, intermodality, and connectivity” includes the promotion of transit-oriented development (TOD), the improvement or extension of public transport networks, and the improvement of stations and stops by developing better sidewalks, parking, taxi points, bicycle parking, and public toilets, among other amenities.

- Axis 6, “Infrastructures for active modes”, considers measures to promote bicycle-friendly cities (e.g., the creation of bicycle lanes and support infrastructures), and pedestrian-friendly city (e.g., safe and accessible routes and support equipment).

- Axis 7, “Transport electrification”, arises from the need for energy independence in transport.

- Axis 8, “Land-use planning”, brings together actions related to sustainable urban models anchored in the principles of mixed land use.

- Axis 9, “Data collection”, refers to the identification and/or creation of indicators to support diagnosis and evaluations by considering, for example, real-time and open-access information using digital tools (Global Positioning System (GPS), apps), in which case, the transport user is also the information producer.

- Axis 10, “Legislation”, frames the legislative measures that cover all users and all transportation modes.

- Axis 11, “Agents and Competencies”, reflects the initiatives that promote partnerships between funders, managers, and beneficiaries; multi-level, multi-agent, and multi-sector partnerships; and urban mobility in all policies.

- Axis 12, “Instruments and studies”, includes initiatives related to sustainable urban mobility plans or similar, school or business mobility plans, road safety plans, and other tools, such as the Health Impact Assessment (HIA) and Health Economic Assessment Tool (HEAT).

- Axis 13, “Awareness of benefits for health, environment, and economy sectors”, combines actions associated with active mobility, road safety education, and initiatives to communicate strategies and plans related to this subject to the whole community.

CONCLUSIONS

The researchers conclude that the answer to the research question (are sustainable urban mobility policies contributing to healthy cities?) is clearly affirmative as it is proven that sustainable development principles are an umbrella of all policies and diffuse in a top–down way, especially through the policies directed by the European Commission and Portuguese government.

This fact translates to the policy instruments and practices being consistent with the principles of healthy cities, which is a movement characterized by its bottom–up nature and anchored in a local, innovative, multi-sectoral, and multiscalar governance strategy. These principles are not implemented explicitly or consciously by the technicians and politicians who work in the field of urban mobility in the LMA; nevertheless, the findings of this study indicate that they are being carried out.

Lessons for the Future

The authors stress that the promotion of cross-sectoral and multi-sectoral policies is one of the key factors in this study, although it proves to be scarce in both the analyzed instruments and agent discourses and practices. In this sense, the following is suggested:

a) The inclusion of Healthy Cities projects teams and/or their feedback in the elaboration, discussion, and evaluation phases of sustainable urban mobility planning instruments or other instruments;

b) The inclusion of representatives of the urban mobility domain in a broad team of Healthy Cities projects (along with representatives of other areas, such as education, green spaces, or sanitation)

c) Encouraging the inclusion of the sustainable urban mobility approach and its influence on healthy cities not only in the network of partners of Healthy Cities projects but also in other existing networks (e.g., Social Network, Educational Network, Local Agenda 21). This promotes access to a greater diversity of funding sources and awareness initiatives.

Finally, the importance of the awareness of the community and local agents is highlighted, since it is only with their acceptance that significant changes can be expected. Some of the main agents are as follows:

a) Companies, especially those with a large number of workers, are considered to be major centers of attraction/generation.

b) The transport operators, in order to promote better levels of quality of the transport system, can also become involved in campaigns to raise awareness of the factors leading to the unsustainability of individual transport and promote a modal shift to soft modes or collective transportation;

This article underlines the necessity to continue this specific research. If the implicit presence of the healthy city principles in the context of urban mobility planning has been proven, the next approach should be centered on the evaluation of the implementation of the instruments and their results. A more demanding study would be the evaluation of their impacts, especially on health. Only then can we assess the real changes that have been made in favor of healthier territories.